“Nutrition labels have been around for decades, are familiar to most, if not all, Canadians, and have consistently helped people make clearer, faster, and more informed decisions about complex products. They distill dense scientific data, such as sodium content and serving size, into an easy‑to‑read format that supports everyday decision‑making,” reads the opening statement from University of Ottawa professor Marina Pavlovic.

While her stance may be clear, there were four days of hearings during which major telecoms, minor players, advocacy groups, and concerned citizens presented their cases to the CRTC regarding the potential for new nutrition labels for Canadian home internet. The U.S. did something similar in the spring of 2024. However, since it’s only been out for a little while, adoption numbers should be taken with a grain of salt.

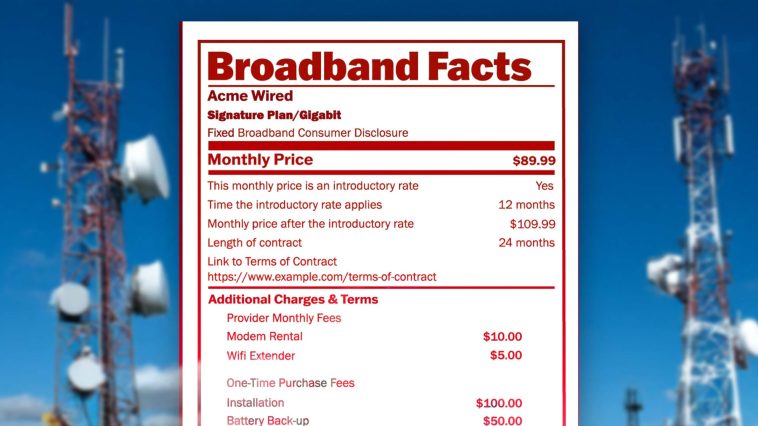

The goal of these labels is to make it easier for everyday Canadians to compare internet plans with one easy-to-read and easy-to-share sheet. In the U.S., this includes things like the monthly price, a breakdown of that price, the length of the contract, bundle discounts, internet speeds and latency. You can see an example of the FFC nutrition label on its website.

The Competition Bureau

Canada’s competition watchdog supports the adoption of nutrition labels. The Bureau says, “From a competition perspective, enabling people to more easily compare services and providers gives them the power to make choices based on their own specific needs and circumstances.”

It alleges that a Canadian version of the home internet nutrition label should look like it does in the U.S. It’s easy to read, and people are somewhat familiar with it because it’s been on food for so long. However, the Bureau suggests that the Canadian version should have an all-in price encompassing everything. In the U.S., prices are broken up slightly, so you’ll see how much your modem rental is separately from your data plan cost, and you’ll need to add those costs manually to see your total monthly bill.

After that, it claims that these labels should be applied to wireless phone customers, not just home internet.

Overall, the Bureau just wants more easily accessible information available to shoppers, and it hopes that having a more fully formed picture that can be easily compared across telecoms will help reduce the barriers to switching carriers.

Telus

Telus advocates for labels but says they could be more relaxed in Canada since the CRTC wireless code already mandates a significant amount of clarity. Specifically, Telus wants to make sure speeds are labelled in a standardized way. It seems like the Vancouver-based telecom sees these new labels as a way to get a competitive advantage since it already offers many high-end fibre plans.

On the flip side, Telus and Bell are tied up in another CRTC effort to make sure telecoms share fibre lines so that there can be more competition in markets only served by one provider. While Telus doesn’t openly mention this, the new labels would theoretically then show that in those markets, all networks are the same, allowing competition based on pricing.

Overall, David Peaker, general counsel for Telus, says, “We are proud of our networks. We are proud of the services we provide to Canadians, and we think that transparency shows us well. It’s good for our consumers, and it would be good if all carriers had similar practices so the consumers could understand exactly what they’re getting and where the performance advantages lay.”

Telus also thinks showing maximum speed and average median on the label will be easy for shoppers to determine network quality. However, the company would be happier if pricing information were omitted. It just thinks there are too many options on the market, so things will get unnecessarily complex. The labels are better suited to providing context on quality in Telus’ view.

Bell

Bell argues against the labels and says that it is already providing a great product, so it thinks labels will just be too confusing. However, as someone who recently shopped for internet at Bell, I can tell you it isn’t very clear. For instance, I signed up for DSL internet; however, on the purchase page, the heading is “Fibre to the neighbourhood Internet plans,” even though all the plans listed run on DSL phone lines. To make matters worse, I bought the ‘Internet 50’ plan, and when the tech came to my house, he was only able to get me around 30Mbps instead of my promised 50Mbps. More transparency would have been beneficial here.

After that, Bell argued that the number one problem with the internet in Canada is that there’s not enough fibre, which is true. The telecom then takes the opportunity to rehash its dissatisfaction with the CRTC ruling on sharing fibre infrastructure and how that will limit infrastructure investments. Bell is currently self-imposing this infrastructure limit as a protest against the CRTC.

One portion of the proceeding that clearly outlines Bell’s intentions is an exchange in the Q&A section of its presentation. Bell’s vice president of legal and regulatory was explaining that Bell advertises its maximum internet bandwidth as an “up to” speed. He is then interrupted by Commissioner Abramson, who mentions that changes to the Telecom Act mandate service providers advertise a typical speed. Bell retorts that it is allowed to promote a typical speed as the top-end speed as long as the speed it’s promoting is the actual typical speed.

This is a small exchange, but shows just how many hoops Bell jumps through to get around regulations.

Further into the presentation, Bell shared that it held meetings to see if it could spin the nutritional labels to a competitive advantage, as Telus appears to be doing. Still, once it looked at it from a cost and consumer experience point of view, it decided it didn’t want to support the labels.

Rogers

Rogers’ presentation follows a similar path to Bell’s, echoing the sentiment that nutrition labels will confuse shoppers. However, in the middle of its presentation, it conceded that having a label with speed and peak period speeds helps show customers how reliable a network can be.

That said, it does argue against showing latency, jitter, packet loss, and other information that is already covered in the wireless code, like price. I agree with them on some of the more technical aspects, but latency and price should be on the label to give consumers an easy way to look at one document to learn everything they need to know about a specific plan. Having a price on the label also helps people keep track of increases over time.

When the CRTC asked Rogers about latency specifically, it said it already provides high-speed service, so most customers don’t have any issues with latency. The company also worries about the cost of testing latency on a national scale. The final point, and the one that might carry the most merit, is that often, latency is introduced by Wi-Fi in the home, which is something that Rogers has limited control over since all houses are different. Not to mention, all data centres are at varying distances around the world, and that can cause latency changes as well.

When the CRTC doubled down and asked specifically if Rogers thinks latency is notable to gamers, the telecom said, “No, I don’t think so. I think gamers understand that it’s a very small component of it, and that’s why a gamer won’t connect, maybe over Wi‑Fi. Maybe they’ll use ethernet. They will also choose, based on how they connect to the U.S. and their access to game servers.”

One area where Bell and Rogers differ is their approaches to what types of internet might benefit the most from some sort of nutrition label. Bell thinks there is more variability in satellite and wireless home internet, and Rogers thinks regulating regular broadband home internet will be more beneficial.

The smaller players

Several smaller players also participated in the hearings. The smallest was an individual named Mr. Hudson, who went to the hearings to argue on behalf of regular consumers. He argued for nutrition labels and also argued that the language on them shouldn’t be watered down. He thinks presenting consumers with the actual technical information presents an opportunity for them to learn about it. The more it is hidden, the less informed the public is about how their internet works and stacks up to the competition.

A smaller regional internet provider in Canada’s North, SSi, and its subsidiaries, argued against the introduction of nutrition labels because it worries that it will make things more confusing for people. That said, in my brief browse of the company’s Qiniq Internet website, I found it confusing. I think distilling much of the information on its site into a label would be very beneficial.

However, Dean Proctor, representing SSi, said in his presentation that “a label like that is the antithesis of innovation.”

Open Media, a community‑driven organization working to keep the internet open and affordable, argues that nutrition labels should be slapped on wireless plans and not just home internet.

The Canadian Telecom Association, a group comprised of all of the telecoms in a large trench coat, argues against the labels. Similarly to the major telecom presentations, it alleges that prices and plans are already easy to understand.

The Independent Telecommunications Providers Association (ITPA), which represents 21 smaller internet companies, claimed that these labels should only apply to large ISPs, and if the labels are required, the ITPA hopes the CRTC will make it iron-clad so all the providers need to present the exact same, easily comparable information. The Association worries that if the rules are too loose, the large ISPs will be able to hide them or use them to mislead customers.

Final Notes

From reading through the transcripts, it really seems like the CRTC took a lot of value from the individual consumer testimonies like Mr. Hudson’s. From my perspective, it feels like the commission members faced similar issues to Hudson when they tried to shop for internet, and some members seemed validated to have others talk about the same struggles.

The part that worried me throughout the presentations was that often a commission member would ask questions about other standardized options to make the telecoms more comparable, without the need for nutrition labels. While I’m all for a standardized approach to make it easy to compare telecom pricing, I worry that without a hard line drawn, the big telecoms will find ways to bury this information.

Source: CRTC June 10 – 13 hearings – June 10, June 11, June 12, June 13.

MobileSyrup may earn a commission from purchases made via our links, which helps fund the journalism we provide free on our website. These links do not influence our editorial content. Support us here.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings