Join our daily and weekly newsletters for the latest updates and exclusive content on industry-leading AI coverage. Learn More

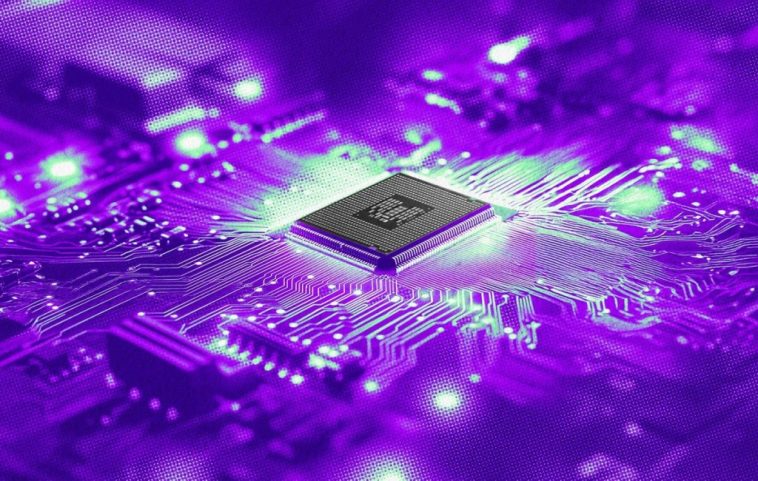

Semiconductor chip sales are set to soar in 2025, led by generative AI and data center build-outs, even as demand from PC and mobile markets may be weak, according to Deloitte’s 2025 chip outlook report.

The semiconductor industry had a robust 2024, with expected double digit (19%) growth, and sales of $627 billion for the year. But that’s even better than the earlier forecast of $611 billion. And 2025 could be even better, with predicted sales of $697 billion, reaching a new all-time high, and well on track to reach the widely accepted aspirational goal of $1 trillion in chip sales by 2030. To get there, the chip industry only has to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 7.5% from 2025 to 2030.

Of course, all of this assumes that the U.S. doesn’t get into a massive trade war as a result of Donald Trump’s plan to place tariffs on computer chips and other semiconductors. He reaffirmed last week that he not only planned to place tariffs on China of 10%, but that he would also put them on Taiwan, where big U.S. companies like Nvidia get their chips. The Consumer Technology Association estimates that tariffs could make game consoles 40% more expensive for U.S. consumers, with a 26% price increase for smartphones and 46% price increase for laptops.

I am guessing this probably came up as Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, visited Trump on Friday just ahead of the tariff announcements on Saturday. And so far, Trump has not yet placed any tariffs on Taiwan or the chip industry. But it’s a fluid situation and it’s complicated.

“When you look at the idea of tariff in general across all industries, if you put a tariff on maple syrup, it’s either maple syrup or it isn’t maple syrup, and it either comes from outside the U.S. or it doesn’t. There are many, many, many kinds of chips. They are manufactured almost always in a highly complex supply chain with bits of them going from country A to B to C, back to A, over to D,” said Duncan Stewart, TMT Center research director at Deloitte, in an interview with GamesBeat. “Given the global nature of supply chains, anything along the line of chip restrictions or tariffs, likely will have an impact and would make supply chains more complex to administer and just in general complicate them.”

Assuming the industry continues to grow at 7.5% CAGR, it could reach $2 trillion in 2040. The stock market is often a leading indicator of industry performance: As of mid-December 2024, the combined market capitalization of the top 10 global chip companies was $6.5 trillion, up 93% from $3.4 trillion in mid-December 2023 and 235% higher than the $1.9 trillion we saw in mid-November 2022. Much of the reason for that was the growth of Nvidia, the AI chip maker, in my opinion.

Are subsidies working for reshoring chip production in the U.S.?

Jeroen Kusters, U.S. semiconductor leader at Deloitte, said in an interview with GamesBeat there are a lot of investments happening on reshoring of chip factories in the U.S. The big ones are under way with companies like Intel, Globalfoundries and TSMC building factories in the U.S. Stewart said that chip executives have said that the investments so far are just the first of what should be even larger numbers in terms of the investment required to bring semiconductor manufacturing back.

“After all of the plants that are in the process of being built and started and launched, at the end of all of that, by 2032, the U.S. may be up around 14% or something. It takes time. It is an absolutely massive industry. And moving the needle from 10% to 14% is in fact a remarkably good number. It’s a sign of how hard it is to move. And it’s the same for Europe, of course,” Stewart said.

How much should the industry invest in AI?

Jeroen Kusters, U.S. semiconductor leader at Deloitte.

This is the trillion dollar questions.

Regarding the risks of smaller models working like DeepSeek and the impact on AI chip demand, Stewart said, “Various people saying AI would be $400 billion or even $500 billion in addressable market, which would be on the order of 2028 or something like that. One of the complicating factors is that there are smaller models out there and more efficient models as well as edge computing. And all of those could change the demand. In other words, you still need GenAI chips, but you need different GenAI chips. Or it could even reduce the demand for GenAI. We actually said that in our outlook as a potential risk factor.”

He added, “Without commenting on any given small model, this has all been known for some time. Somebody comes out and says I have a thing where I used to use many, many expensive chips, and I can now use either newer chips or cheaper chips — that could change the size of the GenAI chip industry. We actually anticipated that.”

He noted that while many of the large hyperscaler data center operators re saying that they are reducing their capital expenditure plans for the next quarter of the next year.

“Although there is always and will always be a threat, one of the things that in recent weeks is the idea that maybe you don’t need as much generative AI infrastructure because of more efficient, smaller models,” Stewart said. “Two weeks before that, there was some remarkable gains in GenAI programming where they did what’s called chain of reasoning. And this was like last month. Those are significantly more accurate. And in fact they can use ten, a hundred, or even a thousand times as many chips as the previous models. So I think I’m comfortable saying that given which week it is, sometimes the focus is on more efficient AI models, but at the same time are news events that make it look like we need even more chips to do better AI.”

Jeroen Kusters, U.S. semiconductor leader at Deloitte, said in an interview with GamesBeat, “I think you’ll find that in terms of demand, there will be step changes in demand. This is sort of a step change in efficiency. We all expect it, and actually we absolutely need models to become more efficient. We expected a relatively linear trend on this. Everyone knows that models are going to get more attention. What we saw now see was a step change, and it confused people a little. That’s okay. We’re going to see more of these step changes. And most of the time, what you’ll find is that, indeed, as the models get better, they will require more performance. They will require more compute. We then get more efficient.”

Stewart said, “One of the large platform companies announced that they have five million users of their generative AI tool for a specific application. And people say, oh, it’s a pilot. No, it isn’t. They have five million companies doing this weekly. The idea that we’re still entirely a group of concepts and pilots is just plain wrong. They are one of the world’s largest companies, and this is a tool that not only their customers are using, but is a thing that the company itself says drives the effectiveness of their product.”

A tale of two markets

Duncan Stewart TMT Center research director at Deloitte

That said, it is worth noting that “average” chip stock performance in the last two years has been a “tale of two markets”: companies that are involved in the generative AI chip market outperformed that average, while companies without that exposure (automotive, computer, smartphone, and communications semiconductor companies, for example) underperformed the semiconductor market average.

One driver of industry sales has been the demand for generative AI (gen AI) chips: a mix of CPUs, GPUs, data center communications chips, memory, power chips, and more. The Deloitte 2024 TMT Predictions report predicted that those gen AI chips collectively would be worth “more than” $50 billion, which was a much too conservative forecast, as the market was likely over $125 billion in 2024 – and represented over 20% of total chip sales for the year.

Last year, Deloitte estimated that AI chips would grow by a strong number, but the AI industry sailed right past those optimistic numbers and grew even bigger.

At the time of publication, Deloitte predicts that gen AI chips will be over $150 billion in 2025. Further, AMD CEO Lisa Su has moved her estimate for the total addressable market for AI accelerator chips up to $500 billion in 2028, a number which is larger than sales for the entire chip industry in 2023.

Chip demand is exploding because of AI.

In terms of end markets, after being flat at around 262 million units in 2024 over 2023, PC sales are expected to grow in 2025 by over 4% to about 273 million units. Meanwhile, smartphone sales are expected to grow at low-single digits in 2025 (and beyond) to reach an estimated 1.24 billion units in 2024 (+6.2% year-over-year growth). These two end markets are important for the semi industry: In 2023, communication and computer chip sales (which include data center chips) made up 57% of overall semiconductor sales for the year compared to auto and industrial, which accounted for only 31% of sales combined, for example.

One challenge for the industry is that while gen AI chips and associated revenues (memory, advanced packaging, communications, and more) are responsible for outsized revenues and profits, they represent a small number of very high value chips, meaning that wafer capacity—and therefore utilization—for the industry as a whole isn’t as high as it might appear. In 2023, nearly a trillion chips were sold at an average selling price of US$0.61 per chip. At a rough estimate, although gen AI chips might account for 20% of revenues in 2024, they were less than 0.2% of wafers.

Even though global chip revenues for 2024 was forecast to rise 19%, silicon wafer shipments for the year actually declined an estimated 2.4% for the year. 16 That number is expected to grow by almost 10% in 2025, fueled by demand for components and technologies used largely in gen AI chips, such as chiplets, as mentioned in the 2025 TMT Predictions report. Of course, silicon wafers are not the only kind of capacity to track: Advanced packaging is growing even faster.

As an example, some analysts estimate that TSMC’s CoWoS (chip-on-wafer-on-substrate) 2.5D advanced packaging production capacity will reach 35,000 wafers per month (wpm) in 2024 and could increase to 70,000 wpm (100% YoY) and further by 30% YoY to 90,000 wpm by end of 2026.

Further, driving innovation in the industry is not cheap. In 2015, overall chip industry average spending on R&D was 45% of its EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes), but by 2024 it was an estimated 52% of EBIT. R&D seems to be growing at a 12% CAGR, white EBIT is only growing at 10% (see figure 2).

The semiconductor outlook: R&D and EBIT growth. (figure 2)

Finally, it’s worth reminding readers that the chip industry can be notoriously cyclical. The industry has flipped from growth to shrinkage nine times in the last 34 years (figure 3). 21 So it may seem that the industry is seeing less extreme growth or shrinkage in the last 14 years, compared to the 1990-2010 period, but the frequency of contractions seems to increase. 2025 looks solid for now, it’s hard to tell what 2026 will bring.

Making investments in a resilient supply chain will make sense around the world.

“Companies with or without incentives are deciding to build new plants in new places to shorten or make resilient supply chains. This is an industry where staying on top of the ball has been a thing they’ve been doing for half a decade now. It has been a constantly shifting mix of various incentives and restrictions. That is a fairly normal thing for the semiconductor industry,” Stewart said.

Global semiconductor industry—Historic billings (Three month moving average), 1990 to 2024 October YTD. (figure 3).

These trends and others play into the 2025 semiconductor industry outlook, where the firm drills down into four big topics for the year ahead: generative AI accelerator chips for PCs and smartphones and the enterprise edge; a new “shift left” approach to chip design; the growing global talent shortage; and the need to build resilient supply chains amid escalating geopolitical tensions.

Generative AI chips in PCs, smartphones, the enterprise edge, and IoT

Many of the chips that are being used for training and inference of gen AI cost tens of thousands of dollars and are destined for large cloud data centers. In 2024 and 2025, these chips or lightweight versions of these chips are also finding homes in the enterprise edge, in computers, in smartphones, and (over time) in other edge devices such as Internet of Things (IoT) applications. To be clear, in many cases these chips are being used for either gen AI, traditional AI (machine learning) or, increasingly, a combination of both.

The enterprise edge market was already a factor in 2024, but the question in 2025 will be about smaller, cheaper, less powerful versions of these chips becoming a key part of computers and smartphones. What they lack in per-chip value, they can make up for in volume: PC sales are expected to be over 260 million units in 2025, while smartphones are expected to be over 1.24 billion units.

Sometimes the “gen AI chip” can be a standalone single piece of silicon, but more commonly it’s a few square millimeters of dedicated AI processing real estate that is tiny part of a much larger chip.

Enterprise edge: Although generative AI via the cloud will likely continue to be a dominant option for many enterprises, about half of the enterprises worldwide are predicted to add AI data center infrastructure on-premises—an example of enterprise edge computing. 23 This could be, in part, to help protect their intellectual property and sensitive data and comply with data sovereignty or other regulations, but also to help them save money.

These chips are largely the same as those found in hyperscale data centers, with server racks costing millions of dollars and requiring hundreds of kilowatts. Although smaller than hyperscale chip demand, we estimate the chips for enterprise edge server chips will likely be worth tens of billions of dollars globally in 2025.

Demand for NPU-enabled PCs. (figure 4)

Personal computers: Sales of gen AI powered PCs are predicted to be half of all PCs in 2025, 26 with some forecasts suggesting that almost all PCs will have at least some on-board gen AI processing—also known as neural processing units (NPUs)—by 2028 (see figure 4). 27 These NPU-powered machines are expected to command a price premium of 10-15%, but it’s important to note that not all gen AI PCs are equal.

There’s a dividing line at the 40 TOPS (trillion operations per second) level, following a recommendation from major PC ecosystem companies that only computers with more than TOPS be considered true AI-enabled PCs. 29 As at the time of writing, some buyers are cautious about the new PCs, either unwilling to pay the premium, or waiting until more powerful gen AI NPUs are introduced in the back half of 2025.

As of December 2024, many of the installed base of PCs were running on x86 CPUs, with the balance being on CPUs based on the Arm architecture. MediaTek, Microsoft, and Qualcomm announced in 2024 that they would make Arm-powered PCs, specifically gen AI PCs. It’s unclear how successful these achines will be in the next 12 months, but it will likely be a key issue for the various chipmakers, with Qualcomm predicting it will sell $4 billion worth of PC chips annually by 2029.

Smartphones: Where PC NPUs might be worth tens of dollars in value, smartphone equivalent gen AI chips may be worth much less, and Deloitte estimated under $1 worth of silicon on next generation smartphone processors. Even though the smartphone market is over a billion units sold annually, and even though we predict gen AI smartphones will be 30% of phones sold in 2025, the semiconductor impact is likely smaller than PCs in dollar terms. Instead, an interesting angle for chipmakers could be to see if consumers are excited enough about new gen AI phones and features to shorten the replacement cycle. Consumers have been keeping phones longer before upgrading, and sales have been flat for

years now. 35 If gen AI enthusiasm causes an uptick in smartphone sales, that could benefit all kinds of chip companies, not just those that make the gen AI chips themselves.

IoT: A gen AI chip in a data center might cost $30,000. A gen AI chip on a PC might cost $30. A gen AI chip on a smartphone might be $3. For gen AI chips to work on the low-cost Internet of Things market, they should cost about $0.30. That’s unlikely to happen anytime soon, but with the possibility of tens of billions of IoT endpoints needing AI processors, this is a market to watch for the longer term.

“As good as Gen AI is,” Stewart said, other categories like PCs and smartphones are up a little or mostly flat, and automotive is actually down from a year ago.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” Stewart said. “Sometimes that is true, even when there are pockets of enormous growth in the semiconductor industry. It’s really important to remember there are other kinds of chips that are not growing at the same level. To some extent, the growth in GenAI is a spectacular success story, but it is masking some pockets of weakness out there in other parts of semiconductor manufacturing. And we just think it’s really important to remind people about that, because as an industry, there are companies that make GenAI chips and don’t make the other kinds and then there are companies that make the slower growing ones and aren’t benefiting from AI.”

As far as strategic questions for the industry go, Deloitte asked, “Although gen AI chips for data centers are in demand now, given their importance to industry growth, are there any signs that demand is weakening, or that processing is moving away from data centers to edge devices?”

Chip design ‘shifts left’ and calls for a greater collaboration across the industry

Deloitte predicted that, by 2023, AI would emerge as a powerful aid to human semiconductor engineers, assisting them on extreme complex chip design processes, and enabling them to find ways to improve and optimize PPA (power, performance and area). As of 2024, gen AI has enabled rapid iterations to enhance existing designs and discover entirely new ones and can do it in less time.

In 2025, there will likely be more emphasis towards ‘shift left’—an approach to chip design and development where testing, verification, and validation are moved up earlier in the chip design and development process — as optimization strategies could evolve from simple PPA metrics to system-level metrics like performance per watt, FLOPs per watt (FLOPs denotes floating point operations per second), and thermal factors. And the combination of advanced AI capabilities—graph neural networks (GNN) and reinforcement learning (RL)—will likely continue to help design chips that are more power-efficient than typical chips produced by human engineers.

Domain-specific and specialized chips are expected to continue to gain prominence over general-purpose ones, as several industries (such as automotive) and certain AI workloads would require customized approaches to designing chips. However, a widespread adoption of application-specific integrated circuits (or ASICs) remains less clear, as the development and maintenance of such hardware can be costly and could divert focus from other AI advancements. But here’s where gen AI tools can allow companies to design more specialized and competitive products including custom silicon.

3D ICs and heterogeneous architectures are introducing challenges related to arranging, assembling, validating, and testing the various chiplets, which can sometimes be pre-assembled. This shift towards system design over individual product design can incorporate software and digital twins early on—stressing the importance of early and frequent testing.

By 2025, synchronizing hardware, system, and software development upstream in the process will likely help redefine future system engineering and enhance overall efficiency, quality, and time-to-market.

To evolve and keep pace with the changing face of design, the industry may want to consider new ways to handle the complex design processes. Already, the chip industry is exploring digital twins to emulate and visualize complex design processes step-by-step, including the ability to move around or swap chiplets to measure and assess performance of a multi-chiplet system. And digital twins could increasingly be used to give a visual representation (via 3D modeling) of the physical end-device or the system to assist with all aspects of design, including mechanical as well as electrical (software and hardware).

Designers should work with EDA (electronic design automation) and other hi-tech CAD/CAE (computer-aided design/computer-aided engineering) companies to strengthen design, simulation, and verification and validation tools and capabilities for hybrid and complex heterogenous systems. And they also should consider using and adapting model-based system engineering (MBSE) tools as part of the broader EDA ‘shift left’ approach.

As design and software are expected to play crucial roles in the development of next-generation advanced chip products, bolstering cyber defense becomes more important, heading into 2025. To help align with shift left approach, chip designers should integrate security and safety testing early in the chip design process. They should implement redundancy and error correction and detection mechanisms to help ensure that systems can continue to operate even when some of the components fail, and hardware-based security features such as secure boot mechanisms and encryption engines.

Deloitte said among the strategic questions to consider: As AI in chip design becomes more prevalent and common and EDA becomes more and more AI-enabled, how can the industry proactively ensure trust and transparency in the complex design process by always keeping human engineers in the loop and giving them a major role in the overall process?

The intensifying talent challenges in semiconductor industry

A skill gap in chips looms. (figure 5)

In Deloitte’s 2023 Semiconductor industry outlook report, the firm wrote that the industry needs to add a million skilled workers by 2030, or more than 100,000 every year. Two years after, not only does that forecast hold good, but the talent challenge is expected to intensify further in 2025. Globally, countries are not producing enough skilled talent to meet their workforce needs.

From core engineering to chip design and manufacturing, operations, and maintenance, AI may help alleviate some engineering talent shortages, but the skill gap looms (see figure 5). Attracting and retaining talent will likely continue to be a challenge for many organizations in 2025, and a big part of the problem is an aging workforce, which is more prominent in the United States and even Europe. Add the complex geopolitical landscape and supply chain fragility to this equation, and it becomes clear that the availability of talent supply is under stress globally. With onshoring and reshoring of fabrication, assembly, and test in the US and Europe, there will likely be pressure on chip companies and foundries as they source more of the talent locally in 2025.

For example, talent challenges are contributing to delays in opening new plants. On a related note, “friendshoring” (collaborating with companies from countries considered to be allies) can provide stability and resilience to supply chains, especially for the United States and European Union. But it also demands scouting for the right skills to help meet new capacity demands and talent roles in destinations such as Malaysia, India, Japan, and Poland.

Chip companies can’t continue to wrestle over the same finite talent pool and still expect to match up to the industry’s pace of technological advancement and capacity expansion. So, what can semiconductor companies do in 2025 to address the talent conundrum?

To help attract AI and chip talent, chip companies should consider offering a sense of trust, stability, and projected market growth; with this, they can help make the industry more appealing to recent high school grads and fresh entrants to help reinvigorate talent pipelines.

Countries aiming to benefit from their respective domestic chips acts should consider weaving in strategic goals and aspects related to workforce development and activation. Some examples could include training programs, expanded vocational and professional education, and employment opportunities that their local chip companies would commit to receive funding. Semi companies should consider collaborating with educational institutions (high schools, technical colleges, and universities) and local government organizations to leverage chip funds to develop and curate targeted workforce training and development programs aligned with specific industry needs in the region.

Semi companies should design flexible upskilling and reskilling programs for career path flexibility to help address future workforce skills and gaps. Additionally, they should implement and leverage advanced tech and AI-based tools to assess diverse talent related factors such as supply, demand, and current and projected spend, to perform complex workforce scenario modeling to support strategic talent decision-making.

Deloitte said among the strategic questions to consider: How should the workforce be characterized and segmented based on specialization areas, for example, design and IP, and manufacturing, operator, engineering, and technical roles? And how can the industry customize talent sourcing and skill development strategies based on these roles, as well as based on specific geographic regions where hiring takes place?

Stewart said one thing that could hold back the reshoring of the chip industry in the U.S. is a big talent shortage. But he noted that talent shortage is global as every country is struggling to find enough people. That means retraining and research investments have to be made in order to keep the growth going.

Building resilient supply chains amid geopolitical tensions

Deloitte 2024 Semiconductor Outlook report already talked about geopolitical tensions in depth, so what’s new for 2025?

The same…but even more. As one example, in December of 2024 the outgoing administration issued a new list of US export restrictions mainly still focused on advanced nodes (despite some speculation that restrictions might be broadened to include some relatively less advanced nodes). These restrictions now include additional separate categories around advanced inspection and metrology. Additionally, many (over 100) new entities (mainly Chinese) have been added to the restricted entity list.

As part of these restrictions, the US seems to be adopting the “small yard, high fence” approach toward semiconductor export restrictions. This aims to impose a high level of restrictions on a relatively small subset of chip technologies with a focus on those that defense, including advanced weapon systems, and advanced AI used in military applications.

The new restrictions (if implemented by the new administration) go on to flag that AI advancements are increasingly being viewed as matters of national security. The day after those new restrictions, China announced further restrictions on the export of gallium and germanium (as well as other materials), both key for the manufacture of multiple semiconductors.

As Deloitte predicted in 2024, ongoing materials restrictions will likely pose a challenge for the chip industry, but also an imperative for the industry to do more recycling of e-waste. In mid-January of 2025, the outgoing administration announced Interim Final Rule on AI Technology Diffusion. The Interim Final Rule will impose new controls for chip exports.

At time of writing, it is unknown whether the incoming administration will roll back the December and January restrictions, modify them, or even propose additional restrictions.

Additionally, the new administration has proposed increasing its use of tariffs, including tariffs on goods from China, Mexico, and Canada. Given the global nature of most semi supply chains, the proposed new AI related chip export controls (by the outgoing administration) and the planned higher tariffs would likely have an impact and could make supply chains more complex to administer, shifting profits, costs, and more. And the impact could be felt across the supply chain – including R&D and manufacturing – as well as how industry policies are shaped across countries and regions.

Of course, there are additional geopolitical risks or changes: Conflicts in Ukraine/Russia and the Middle-East continue, potentially affecting semiconductor manufacturing, supply chains, and critical raw materials. But the chip industry has other vulnerable points: the December martial law order in South Korea highlighted the global supply chain dependency and concentration of certain types of semiconductors, especially in the most advanced technologies.

As an example of concentration, almost 75% of DRAM memory chips globally are made in South Korea. It’s not just geopolitics that can interrupt key materials: 2024’s Hurricane Helene briefly shut down two mines in North Carolina that are sources for nearly all of the world’s ultra-high purity quartz, essential for making the crucibles which are a key part of the chipmaking process. With hurricanes, typhoons, and other extreme weather events projected to become more frequent and intense due to climate change, expanding the sources for key materials is likely to continue to be a supply chain priority.

It is worth noting that, as of late 2024, a key part of the export restrictions from the United States and allies is having an effect: The restrictions around extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines seem to be posing a barrier, preventing Chinese companies from making advanced node chips at scale and with acceptable yields. Although there are 7 nm and 6 nm chips being made in limited numbers using older deep ultraviolet (DUV) technology, the volumes are low, yields are uneconomical, and that situation is expected to persist at least until 2026.

To be clear, semiconductor supply chains worked well in 2024, even as the industry grew by almost 20%. At this time, there’s no reason to believe 2025 supply chains will be less resilient, but as always, the risk is there. And given how important gen AI chips are expected to be in 2025 and beyond (up to 50% of sales, perhaps 76 ) and the relatively higher concentration of processor, memory, and packaging required for cutting-edge chips, the industry may be more vulnerable to supply chain disruptions than ever before. Although the industry is likely to become less concentrated geographically thanks to the various chips acts – and initiatives like onshoring, re-shoring, near shoring, and friendshoring are all still in their early days – the industry remains highly vulnerable for the next year or two, at least.

Deloitte said that among the strategic questions to consider was, “Given the fluid geopolitical environment and escalating export restrictions, what should be the mix of reshoring vs. offshoring? And how should the industry factor potential disruptions to any existing supply chain channel partner relationships in erstwhile friendly countries and allies, aka friendshoring?”

Signposts for the future

For 2025, semiconductor industry executives should be mindful of the following signposts:

There is currently a mismatch between very high spending on semiconductors for gen AI, and companies being able to monetize their gen AI offerings. For 2025, the argument of “the risk of underinvesting is greater than the risk of overinvesting” seems to be still dominant, but if that attitude shifts, demand for gen AI chips could become weaker than predicted.

Competition from agile chip startups could intensify, challenging incumbents in the broader semiconductor industry. Notably, AI chip startups secured a cumulative $7.6 billion in venture capital funding globally during Q2, Q3 and Q4 of 2024, and several of these startups offer specialized solutions including customizable RISC-V-based applications, chiplets, LLM inference chips, photonic ICs, chip design, and chip equipment.

With interest rates in the United States and other major markets likely to drop further, a favorable credit environment could act as a tailwind for the chip industry’s M&A scene, which has already seen an uptick.

Moreover, with two different chip markets evolving—one for AI chips and one for all other types of

chips—the industry may experience M&A and consolidation, especially if companies with valuable IP lag their peers and are seen as attractive targets. Nonetheless, potential tighter regulations and trade conflicts, globally, could potentially dampen the deal environment.

As geopolitical challenges ripple across the globe, chip companies should brace themselves for further disruptions. Traditional channel partner models and allyships could get upended, even as reshoring, friendshoring, and nearshoring have gained momentum. Prolonging regional conflicts and wars could further impact the flow of vital materials and inventories. All of these could disrupt semi companies’ demand planning, requiring them to be more agile and adapt supply chain and sourcing contracts, and pricing terms.

A significant part of capex spending and revenues was driven by AI and the advanced wafers needed to produce those highly advanced AI chips. However, wafer demand from auto, industrial, and consumer segments continue to be lackluster, while there’s some uptick in demand from mobile handset and other consumer products.

Through 2025 and 2026, though the overall revenue and capex seem to continue trending upward (at least for the next nine to 12 months), any downward movement in AI-related spending and components shortage could have an adverse impact ripping through the broader global semiconductor and electronics supply chain.

The pandemic caused havoc in the supply chain for a couple of years. But Stewart said good things have happened to global semiconductor supply chains in the last four years. They are more resilient than they were last time, he said.

“And every single semiconductor supply chain expert in the world says that this is a good thing and we can continue to do it. And that there will also be another supply chain interruption and shortage that has severe problems at some point within the reasonable future,” he said. “You can make the supply chain more resilient. You cannot make it bulletproof. Things happen. There are droughts and fights and trade wars and restrictions and all of the different things that the economy [deals with.]”

Kusters noted that making the supply chain more resilient doesn’t happen overnight. That resilience is still building but it isn’t completely finished yet.

“We have talked about making more resilient supply chains very much a kind of incentive-based program, like the European Chips Act would be an example. We will build this plant in Poland because we don’t have one in Europe, and we need that, and it’s very directive. One of the things that we might see with restrictions and tariffs and other forms of things that shape supply chains is those might end up making different kinds of outcomes than you would have gotten [otherwise],” Stewart said.

Daily insights on business use cases with VB Daily

If you want to impress your boss, VB Daily has you covered. We give you the inside scoop on what companies are doing with generative AI, from regulatory shifts to practical deployments, so you can share insights for maximum ROI.

Read our Privacy Policy

Thanks for subscribing. Check out more VB newsletters here.

An error occured.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings