For the past few months, Meta has been sending recipes to a Dutch scaleup called VSParticle (VSP). These are not food recipes — they’re AI-generated instructions for how to make new nanoporous materials that could potentially supercharge the green transition.

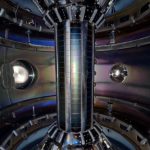

VSP has so far taken 525 of these recipes and synthesised them into nanomaterials called electrocatalysts. Meta’s algorithms predicted these electrocatalysts would be ideal for breaking down CO2 into useful products like methane or ethanol. VSP brought the AI predictions to life using a nanoprinter, a machine which vaporises materials and then deposits them as thin nanoporous films.

Electrocatalysts speed up chemical reactions that involve electricity, such as splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen, converting CO2 into fuels, or generating power in fuel cells. They make these processes more efficient, reducing the energy required and enabling clean energy technologies like hydrogen production and advanced batteries.

The problem is that it typically takes scientists up to 15 years just to create one new nanomaterial — until now.

“We’ve synthesised, tested, and validated hundreds of nanomaterials at a scale and speed never seen before,” Aaike van Vugt, co-founder and CEO of VSP, told TNW. “This rapid prototyping gives researchers a quick way to validate AI predictions and discover low-cost electrocatalysts that might have taken years or even decades to find using traditional methods.”

VSP put each batch of the new materials in an envelope and shipped it to a lab at the University of Toronto for testing. The findings were then integrated into an open-source experimental database, which can now be used to train AI models to become more better at predicting new material combinations.

Larry Zitnick, Research Director at Meta AI, said the research is “breaking new ground” in material discovery. “It marks a significant leap in our ability to predict and validate materials that are critical for clean energy solutions,” he said.

The Alphafold of nanomaterial discovery?

But to really crack the code for material discovery, AI models need to be trained on much larger datasets. Not hundreds but tens or even hundreds of thousands of tested materials.

Van Vugt said that VSP’s machine is the only technology available today that could synthesize such a large number of thin-film nanoporous materials in a reasonable time frame — about two to three years, said the founder.

“This could create an AI that is the equivalent of Google Deepmind’s Alphafold, but for nanoporous materials,” said Van Vugt. He’s referring, of course, to the breakthrough algorithm that cracked a puzzle in protein biology that had confounded scientists for centuries.

If that’s true, then it puts the company in a pretty sweet position. The world’s tech giants — think Google, Microsoft, Meta — are all racing to build bigger, better forms of artificial intelligence in a bid to find solutions to some of the world’s greatest challenges, including climate change. Ironically, these models could also think up solutions for their endless appetite for energy. For companies like Meta, investing in material discovery using AI is a win-win.

VSP is working with many other organisations to build out its dataset and mature its technology. These include the Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi, the San Francisco-based Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the Materials Discovery Research Institute (MDRI) in the Chicago area, and the Dutch Institute for Fundamental Energy Research (DIFFER).

The Dutch firm is also fine-tuning its nanoprinters to be faster and more efficient. The current machines are powered by 300 sparks per second, but the team is working on a new printer that would increase this output time to 20,000 sparks per second. This could supercharge material discovery even further.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings